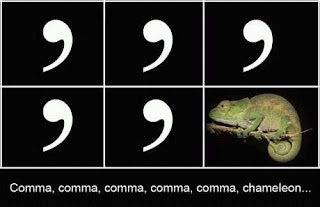

(Commas are important. And box two contains a chameleon; do keep up at the back.)

Grammar? Oh dear.

At the risk of dredging up bad memories for an entire generation, (myself included), I'm sorry to confirm that our 4th-grade teachers were correct: grammar matters. And it is especially important to lawyers when it comes to interpreting legislation and Treaties. For international law, the sacred text in interpreting treaties is itself a Treaty - the 1969

Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) which came into force in 1980.

The grammatical challenge

du jour is with the 1968

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). NPT Article VI reads:

"Each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear disarmament, and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control."

This is a very long sentence. With a single comma.

It could be interpreted in a couple of ways:

First, it could mean that State Parties are are obliged to

pursue good faith negotiations on ceasing the nuclear arms race, and

nuclear disarmament

as well as pursing a treaty on general disarmament under strict and effective international controls.

Second, it could mean that the State Parties are obliged to pursue good faith negotiations on ceasing the nuclear arms race, and nuclear disarmament

within the context of a treaty on general disarmament under strict and effective international controls;

Grammatically, the first interpretation makes more sense than the second, because the comma separates the first clause

"

negotiations in good faith on effective measures relating to

cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear

disarmament,"

from the second

"

and on a treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective international control"

making it clear that the two are separate notions.

This construction would mean that the Nuclear Weapons States (NWS) were obliged to disarm

independent of a treaty on general disarmament. Under this understanding, it would hard to argue that spending £30bn - £100bn between now and 2042 on a replacement for Trident would qualify as "nuclear disarmament", and that as such, such a purchase would be in direct contravention to the UK's international obligations, and would therefore be illegal as a matter of British law.

Unsurprisingly, perhaps, the UK Government favours the second interpretation, tying as it does nuclear disarmament to a future treaty on "general and complete disarmament". As this happy state of affairs is yet to occur (

CCW,

CWC and

BWC notwithstanding) - and the use of the modifier "complete" sets the bar extremely high - so the logic goes, there is no requirement for nuclear disarmament, however desirable this may be. Conveniently, the second formulation does not make it illegal to procure a replacement to the existing

UK Trident SLBM system.

(Minimum deterrence looks a lot like maximum deterrence but with fewer missiles.)

But what's interesting is that over the last decade or so, UK Governments have clung to their tortuous grammatical interpretation whilst publicly demonstrating that the UK is making reductions in its nuclear forces (even as they spend

£1bn per annum to reinvigorate the

AWE Aldermaston nuclear weapons design and production infrastructure). This appears to be an odd halfway house, as it attempts to demonstrate that the UK is moving towards nuclear disarmament whilst retaining what Whitehall describes as a "

minimum credible deterrent".* Moreover, to scrub up its disarmament credentials, the UK draws

attention

to its ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), and

the fact that irrespective of the stalled Fissile Material Cut-Off Treaty

(FMCT), the UK is no longer producing fissile material for military

purposes.**

Indeed, the UK Foreign Office goes so far as to

describe the impact of the 2010 Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) thus:

"In this Review the Prime Minister, David Cameron, and Deputy Prime

Minister, Nick Clegg, committed the UK to maintaining a credible

deterrence by:

- reducing the number of warheads onboard each submarine from 48 to 40

- reducing our requirement for operationally available warheads from fewer than 160 to no more than 120

- reducing our overall nuclear weapon stockpile to no more than 180

- reducing the number of operational missiles on each submarine

These reductions illustrate that whilst the UK believes in

maintaining a minimum credible deterrent this is kept constantly under

review and is fully in line with our international obligations under the

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty."

But it is only in line with the UK's "international obligations under the

Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty" if the second, grammatically tortuous, interpretation of NPT Art VI is accepted.

So who is right? And does it matter?

On which interpretation is correct, I'm not sure yet. But it certainly matters, as if the first interpretation is correct, then the UK Government could find themselves explaining a breach of their international obligations. Against this backdrop, I'm very much looking forward to reading Daniel Joyner's

new book, especially after some of the

critical reviews. I'll write again when I've read it and reflected.

* As mentioned

before this blog does not accept the bald assertion that the UK Trident system currently deters anyone or anything, and therefore doesn't use the term.

** The cynics may observe that it's easy to be in favour of a narrow FMCT if you've got all the highly enriched nuclear fuel that you would ever need on hand, especially if it is already outside of IAEA safeguards.