(IAEA, guardian and enforcer of the much sinned-against NPT)

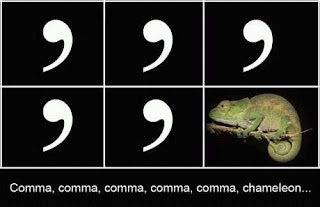

Well, the good news is that the trial is over, and normal service is being resumed; the present status flag will move from Vermont, but I expect that it will be back reasonably soon.As I mentioned a week or so ago, some new work is being kicked off on the British replacement of Trident, with an initial focus on the legal issues surrounding the strange case of the extra comma. Let's pick up the analysis of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) Article VI from where we left off - looking at Daniel Joyner's new book "Interpreting the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty". Joyner's book came in for some reasonably trenchant criticism, which in my view makes it all the more interesting.

It is.

Joyner's argument is beguilingly based on the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) - the Treaty that governs how to interpret Treaties. His (altogether unremarkable) conclusion is that a straight reading of the NPT and it's negotiating history is that as a document it takes the form of three pillars - non-proliferation (Articles I, II and III), peaceful use of nuclear energy (Articles IV and V) and disarmament (Article VI). So far, so conventional. What is more radical is the proposition that the NPT was balanced between these pillars, and that Article VI is just as important as Articles I-III. Joyner's most radical work is in his interpretation of what Article VI actually means (it's that pesky comma again).

But that comes later. Joyner's starting point is the nature of the NPT itself - a contractual rather than merely law-making treaty. In this, Joyner comes to the conclusion that it is the contractual nature of the NPT that provides a key insight into its interpretation; that in making the treaty contractual on a range of differing obligations, it becomes clearer that the Nuclear Weapons States (NWS) owe disarmament obligations to the Non-Nuclear Weapons States (NNWS) in return for the NNWS not pursing their own nuclear weapons programmes (and in the process, locking in their strategic disadvantage / inferiority).

Article VI

Each of the Parties to the Treaty undertakes to pursue negotiations in good faith on effective

measures relating to cessation of the nuclear arms race at an early date and to nuclear

disarmament, and on a Treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective

international control.

Joyner goes on to make a strong case that Art VI commitments are not, pace the Bush Administration's Christopher Ford, merely a commitment to pursue negotiations on nuclear disarmament, but that the good faith test pushes things on to a requirement to conclude a nuclear disarmament treaty separately to the general and complete disarmament treaty that is also envisaged in the NPT.

This view also takes the state practice of the NWS should - it would appear on the basis of self-interest - to be weighed against that of the NNWS, and largely discounted because of the self-interest inherent in their position. I don't think that it's possible to go this far. An with respect, I don't see how the the ICJ's Advisory Opinion in the 1996 Nuclear Weapons Case from paragraph 99 onwards can conclude that

"... the legal import of that obligation goes beyond that of a mere obligation of conduct ; the obligation involved here is an obligation to achieve a precise result - nuclear disarmament in all its aspects - by adopting a particular course of conduct, namely, the pursuit of negotiations on the matter in good faith."

Inasmuch as if this was the construction that the drafters had intended, then they could simply have drafted Art VI thus:

Article VI

Each of the Parties to the Treaty agrees to nuclear

disarmament, and on a Treaty on general and complete disarmament under strict and effective

international control.The point is that they didn't. Much better, I think is the 2005 Joint Opinion by Professor Christine Chinkin at LSE and Rabinder Singh QC, formerly of Matrix Chambers, who note in paragraph 69 that

69. The Treaty obligation is thus not to disarm as such, but a positive obligation to pursue in good faith negotiations towards these ends, and to bring them to a conclusion. Good faith is the legal requirement for the process of carrying out of an existing obligation....

leading them to conclude in paragraph 74:

74. Enhancing nuclear weapons systems, possibly without going through parliamentary processes, is, in our view, not conducive to entering into negotiations for disarmament as required by the NPT, article VI and evinces no intention to 'bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all its aspects'. It is difficult to see how unilateral (or bilateral) action that pre-empts any possibility of an outcome of disarmament can be defined as pursuing negotiations in good faith and to bring them to a conclusion and is, in our view, thereby in violation of the NPT, article VI obligation.

This instinctively feels like the best balance of the difficult negotiating process and subsequent history of the NPT. And it would make a UK Trident replacement a violation of the NPT, and with it a violation of international law.

Interesting times!